OVERVIEW

There are about 2.3 billion children in the world, nearly a third of the total human population. Children are defined by law as people who are under the age of majority in their country, usually 18 years old. Whatever their age, all children have human rights, just as adults do. This includes the right to speak out and express opinions, as well as rights to equality, health, education, a clean environment, a safe place to live and protection from harm. Children’s rights are enshrined in the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), the most ratified human rights treaty in the world. Only one of the UN’s 197 member states hasn’t ratified the Convention — the United States.

The UNCRC seeks to protect children from harm, to provide for their growth and development, and to empower their participation in society. Article 42 of the Convention is a commitment to educate children and adults about child rights, but it seldom happens. Ignorance of rights puts children at greater risk of abuse, discrimination and exploitation.

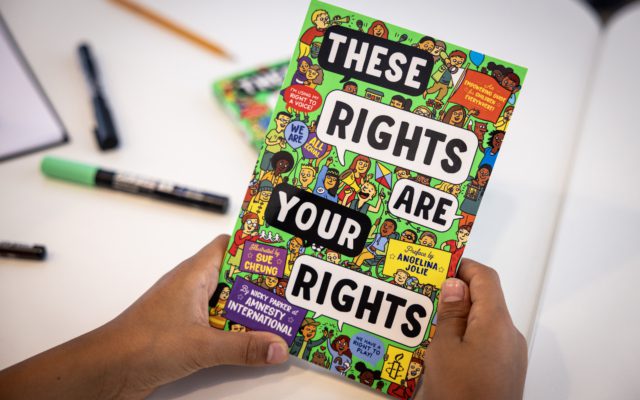

That is why Amnesty International create a series of books about right rights. Know Know Your Rights and Claim Them is a guide for teenagers co-written with Angelina Jolie and Professor Geraldine Van Bueren QC. Similarly, These Rights Are Your Rights is an empowering guide for younger children aged 8+ which includes comic illustrations, fun facts and inspiring stories. It is also why Amnesty International has created a free online child rights education course.

What is the problem?

Globally, children’s human rights are violated every day. Children and young people are especially exposed to rights violations because they are dependent on adults, which can at times heighten risk. Children are likely to form the group at highest risk of poverty, malnourishment and abuse, and are often disproportionately impacted by human rights crises.

How are child rights violated?

Sadly, all child rights are regularly abused or violated. This can start at birth. For example, an estimated 290 million children globally have not had their births registered, so they have no legal identity or proof of existence. This makes it nearly impossible for them to claim their rights throughout their lives – which means they may not be able to go to school, receive healthcare, or get a job when they are older. Girls in low-income countries have only a 50/50 chance of ever having a legal identity and accessing rights and services.

Around the world, over 61 million children do not attend primary school. An estimated 150 million girls and 73 million boys are sexually assaulted every year. In some countries, girls as young as nine are forced into marriage and children as young as six are judged as adults in criminal courts. At least 330,000 children are held in immigration detention in 80 countries every year, simply for being migrants or refugees. Many are forcibly separated from parents and families.

In 2019, one in six children was living in extreme poverty — a situation that puts children at greater risk of domestic violence, child labour, sexual exploitation, teenage pregnancy and child marriage. This number rose significantly during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In 2020, nearly 820 million children did not have basic hand washing facilities at school, contravening their right to health and putting them at greater risk of catching and spreading infection.

WHAT ABOUT CHILDREN’S RIGHT TO A VOICE?

One of the UNCRC’s General Principles is that children have the right to participate – and to be listened to – in all decisions that affect them. Participation rights are linked to children’s levels of maturity and apply accordingly. This is to support their development, but it also helps everyone achieve better-informed decisions. It strengthens society.

Like adults, children have the right to voice their opinions and to peacefully protest. Today, all over the world young people and children are using this right. They are rising up to demand climate justice and racial equality, amongst other calls. Yet their perspectives are still often overlooked or dismissed.

CASE STUDIES 1 – JANNA JIHAD, PALESTINE

I started journalism at the age of seven because I wanted the whole world to know what is happening here and how we live in fear and uncertainty. I want a normal life, a normal childhood.

Janna Jihad

Janna Jihad grew up in the Palestinian village of Nabi Salih, located north of Ramallah city in the West Bank. It is part of Palestinian territory that has been under Israel’s military occupation since 1967.

Janna, and Palestinian children like her, are denied their rights and face discrimination on a daily basis. The Israeli army regularly arrests children from Janna’s village, often during raids on their homes in the middle of the night while families are asleep. Children struggle to access their rights to education and freedom of movement because of barriers and checkpoints which force delays on any journey. It can take hours to get to school instead of a few minutes. People find it hard to travel for work and to earn a living to support their families. For anyone who is sick, it can be nearly impossible to get to a hospital.

In 2009, when Janna was three, her community used their right to peaceful protest and began weekly demonstrations. But they were met with violence. When she was seven, Janna’s uncle and her friend were killed by the Israeli military. Janna used her mother’s phone to record what was happening and reveal the truth. By the time she was a teenager, her live videos were being watched by hundreds of thousands of people around the world. In 2018, Janna became the youngest press card-carrying journalist in the world, at the age of 12. Yet she has faced many threats for her work.

CASE STUDIES 1 – KHAIRIYAH RAHMANYAH, THAILAND

As children, we must be allowed to learn

Khairiyah Rahmanyah

about our rights and it’s up to adults to encourage, empower and support us.

Khairiyah Rahmanyah was born to a fishing family in southern Thailand. The sea near her home is a rich source of seafood and home to endangered marine species, such as sea turtles and rare pink dolphins. In 2020, when she was 17, Khairiyah launched a campaign against the Thai government’s plan to develop land on which her village in Chana is located, into an industrial estate. She spent hours picketing and travelled 1,000 kilometres to Government House in Bangkok to deliver a letter to the prime minister begging him to stop the development. As a result, the government decided to postpone its decision.

Khairiyah said: “I am really proud to be representing the stories of my community. I was born into activism and I have been fighting to protect my community since I was little. It has been painful to live this reality and I want life to be different for the next generation. As children, we must be allowed to learn about our rights and it’s up to adults to encourage, empower and support us.”.

WHAT IS AMNESTY DOING?

GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION

Knowledge is key.

Article 42 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child asks governments to ‘… undertake to make the principles and provisions of the Convention widely known, by appropriate and active means, to adults and children alike’.

To support Article 42, Amnesty International, Angelina Jolie and Professor Geraldine Van Bueren QC (one of the original drafters of the UNCRC) have written a book for teenagers: Know Your Rights and Claim Them. It explains child rights, shows the reality of what happens when they are denied, highlights the powerful work of young activists, and provides tools for young readers to navigate the law, take action and claim their rights.

The book was first published in September 2021, and is available in multiple language versions including Danish, English (UK and USA), German, Korean, Greek, Italian, Romanian, Turkish, Albanian and Polish, with more expected to follow. We hope the book will be published in all countries.

Amnesty International has also created a book for younger children aged 8 and up, These Rights Are Your Rights, which launches in English in the UK, Australia and New Zealand on 5 September 2024, followed by additional language editions to come. Lighter in tone and illustrated throughout, it balances factual content and jokes that appeal to younger readers with inspiring real-life stories and safeguarding tips on staying safe and well.

Amnesty International has also created an introductory online child rights course, for young people and adults. It is free, takes 90 minutes, and includes interviews with child activists, self-paced learning and ideas for taking action on children’s rights.

CASE STUDIES – YEZIDI CHILDREN IN IRAQ

Article 39 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) asks governments to ‘take all appropriate measures to promote physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration of a child victim of: any form of neglect, exploitation, or abuse; torture or any other form of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; or armed conflicts’.

The plight of Iraq’s Yezidi children highlights the importance of this article. Between 2014 and 2017, the armed group calling itself the Islamic State (IS) committed war crimes and crimes against humanity against the Yezidi community in Iraq. Yezidi children were kidnapped and enslaved, tortured, forced to fight, raped and subjected to other horrific human rights violations. Thousands of children were killed or abducted.

Even though hundreds of others survived and returned to their families in Iraq, their homecoming did not mark the end of their suffering. These child survivors went on to face significant physical and mental health challenges which Amnesty International documented in a report published in July 2020, yet they received no assistance. Yezidi boys, who had been forced to fight by their captors, were often isolated by their own communities on their return. Yezidi women and girls who gave birth to children as a result of sexual enslavement by IS were often driven, coerced or even deceived into separating from their children due to religious and societal pressures.

As part of its advocacy efforts, Amnesty International called for a draft survivors law to be expanded to include children as beneficiaries of any reparations scheme. On 1 March 2021, Iraq’s parliament passed the Yezidi Female Survivors Law, which provides the framework for reparations and assistance to survivors of ISIS captivity – including child survivors – with the aim of getting them the support they are entitled to.

IMPACT OF CONFLICT ON CHILDREN IN NORTHEAST NIGERIA

The conflict in Northeast Nigeria has had a devastating effect on children, as documented in Amnesty International’s report, ‘We Dried Our Tears’.

Boko Haram has abducted hundreds of girls and boys and subjected them to further atrocities in captivity. The group has also wreaked havoc on communities across the region, pillaging villages and attacking civilians and schools.

Rather than protecting children fleeing Boko Haram areas, the Nigerian military has often unlawfully detained them for months or years and subjected them to torture and other ill-treatment. Amnesty International has also shown how the government has failed to ensure that displaced children have access to an adequate education.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Children’s rights are human rights. Children require greater protection than adults due to their physical, intellectual, and emotional immaturity. As vital assets to society, they need special protection to ensure their development and growth. Placing great importance on the protection of children’s rights, the international community has enacted several child-related instruments, including:

- The Declaration of the Rights of the Child, also known as the Geneva Declaration (1924), adopted by the League of Nations;

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948 after the establishment of the United Nations;

- The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of the Child, proclaimed in 1959 (although not legally binding under international law);

- The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), adopted in 1989 as part of international law;

- Two additional international legal instruments (Optional Protocols) adopted in 1990:

- The Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, and

- The Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution, and Child Pornography;

- A third Optional Protocol adopted in December 2011: The Optional Protocol on a Communications Procedure, which opened for signature on February 28, 2012, and entered into force on April 14, 2014.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights proclaims that childhood is entitled to special care and assistance; that the child, for the full and harmonious development of his or her personality, should grow up in a family environment in an atmosphere of happiness, love, and understanding; and that the child should be fully prepared to live an individual life in society, brought up in the spirit of the ideals proclaimed in the Charter of the United Nations — particularly in the spirit of peace, dignity, tolerance, freedom, equality, and solidarity.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child: Key Facts

- The UNCRC is the most widely ratified human rights treaty ever.

- Who has ratified: 196 out of 197 UN member states.

- Who hasn’t ratified: the United States

- There are four General Principles underpinning the UNCRC:

- The right to life, survival and development;

- Non-discrimination;

- The right to be heard;

- The best interests of the child.

- There are three Optional Protocols to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child:

- Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict;

- Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography;

- Optional Protocol on a Communications Procedure.

Today, the CRC and its three Optional Protocols are binding international laws that play a crucial role in setting standards for the protection of children’s rights. The CRC is based on two core principles:

- Children’s rights are not granted by the state or any individual. The Convention refers to them as “inherent rights.” Therefore, children enjoy these rights by birth, and no one may abrogate, restrict, or violate them.

- The rights and best interests of the child must be the primary consideration in all actions concerning children.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) protects and promotes the fundamental rights of all children around the world by setting minimum standards. (Countries may provide a higher level of protection but not a lower one.) The CRC obliges State Parties to respect and ensure the rights of every child within their jurisdiction without discrimination of any kind, irrespective of the child’s or their parent’s or legal guardian’s race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth, or other status.

The CRC outlines the obligation of State Parties to protect four major categories of children’s rights:

- Right to Life and Survival: The Convention affirms that every child has the inherent right to life from birth. States must ensure, to the maximum extent possible, the survival and development of the child. Children have the right to receive care — whether from parents, relatives, or the state — to survive and grow and to enjoy an adequate standard of living. If the family cannot provide the minimum standard, the state must step in to assist.

- Right to Protection: Children have the right to be protected from all forms of harm, including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, as well as all forms of exploitation.

- Right to Development: The CRC emphasizes the duty of parents — or, in some cases, the state — to ensure a standard of living adequate for the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral, and social development. It also stresses the child’s right to quality education for the development of their personality, talents, and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential.

- Right to Participation: The CRC emphasizes the child’s right to express their views freely in all matters affecting them, as well as the freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds through any media. Children also have the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. Their right to participation includes the rights to peaceful assembly and association.

On the right to participation, Article 13 of the CRC states: “The child shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of the child’s choice.”

To address the lack of children’s influence in decision-making processes, Article 12 of the Convention stipulates: “States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.” (This article is also incorporated into Article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.)

Furthermore, Article 14 stipulates that: “States Parties shall respect the right of the child to freedom of thought, conscience and religion,” While Article 15 requires that: “States Parties recognize the rights of the child to freedom of association and to freedom of peaceful assembly. No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of these rights other than those imposed in conformity with the law and which are necessary in a democratic society — in the interests of national security or public safety, public order, the protection of public health or morals, or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”

Relevant Thai Laws on Children’s Rights

Section 4 of the Child Protection Act B.E. 2546 (2003) defines a “child” as a person under the age of 18, but not including those who attain majority through marriage. This aligns with the CRC definition, which defines a child as any human being below the age of eighteen years, unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier. According to Section 19 of the Thai Civil and Commercial Code, Chapter I on Natural Persons, a person reaches majority at the age of 20. However, a person who marries before turning 20 attains majority upon marriage, according to Section 20. (A minor becomes sui juris upon marriage, provided the marriage complies with the provisions of Section 1448.)

Section 22, paragraph 1 of the Child Protection Act states: “Treatment of the child, in any case, shall give primary importance to the best interests of the child and there shall not be unfair discrimination.” This aligns with the CRC, which mandates that in all actions involving children, the rights and best interests of the child must be the guiding principle, providing the minimum standard that State Parties must meet or exceed. Thailand became a State Party to the CRC on March 27, 1992. It entered into force in the country as international law on April 26, 1992.

Therefore, according to the CRC and the aforementioned Thai laws, it is evident that children have various rights, including the rights to expression and opinion, which must be reasonably heard. They also have the rights to peaceful assembly and association on an equal footing with adults and to exercise their freedoms without discrimination. However, given that children are more vulnerable and face specific risks compared to adults, it is the duty of the state to protect them from harm or threats that may arise from exercising their rights to participation — such as freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL’S CALLS TO THE THAI GOVERNMENT ON CHILDREN’S RIGHTS

Amnesty International urges the Thai government to:

- Ensure that children can exercise their right to peaceful assembly without interference or threats of harm;

- Create a safe and supportive environment that encourages children to freely exercise their rights to peaceful assembly and freedom of expression without intimidation, harassment, or prosecution;

- Provide training on law enforcement practices and principles aligned with international human rights standards — particularly the CRC — and prepare protocols for situations in which children are participating in or present at protests. These should include protecting at-risk individuals and limiting the use of force against them;

- Conduct effective investigations into any incidents of police violence and misconduct against children during protests. Perpetrators must be held accountable through fair legal proceedings, and victims must have access to effective remedies.